18. Rodin´s erotic drawings

The decomposition of the figure in Rodin´s sculpture runs parallel to the resolution into elements in the field of painting. In the 1870´s and 1880´s, Impressionist painters like Pisarro, Renoir, Sisly and Monet – with whom Rodin had an joint exhibition at the Gallery Georges Petit in 1889 - had dissolved their subject in single coloured

strokes.

Jacques Vilain e.a., Claude Monet – Auguste Rodin, centenaire de léxposition de 1889, catalogue of the exhibition at the Musée Rodin from 14 Nov. 1989-21 jan. 1990 Jacques Vilain e.a., Claude Monet – Auguste Rodin, centenaire de léxposition de 1889, catalogue of the exhibition at the Musée Rodin from 14 Nov. 1989-21 jan. 1990

|

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves,

1904-06; Oil on canvas, 66 x 81.5 cm,

Private collection, Switzerland.

Click image to enlarge it!

|

|

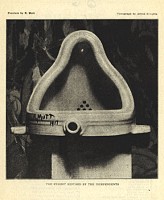

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917.

Photo: Alfred Stieglitz

|

From 1890 on, Paul Cézanne started to organise his

views of the Mont Ste. Victoire in coloured fields –

foreboding Cubism and later abstract art. In 1907, Picasso

finished his Demoiselles d´Avignon, Kazimir Malevich

painted his Black Square in 1915. Two years later - the year of Rodin´s death – Marcel Duchamp sent in an urinal to the New York "Independent Show". Although Duchamp´s Dada-ist action intended to question the very sense of the modernist tendencies of his contemporaries, his ironic gesture was incorporated by art history: from this time on, a mere object could be accepted as an art work.

Within the span of Rodin´s lifetime, following the

invention of photography (1839), the visual arts had

emancipated from the dictate of illusionistic mimesis.

|

But while Rodin expedites the disintegration of the complete figure in his sculpture, he simultaneously abandons the analytical style of his drawings and adopts a more unifying method of sketching.

In

his earlier drawings, Rodin had dissipated the body in single parts, defined by

heavy black outlines. His graphic work dealt with death, sorrow, doubt, pain and

struggle, the tension between inner impulse and outer constraint. But from the

1890´s on, when he can afford to hire a whole range of models and let them move

through his studio, Rodin starts sketching them with swift, generous strokes

that outline the whole body. But while Rodin expedites the disintegration of the complete figure in his sculpture, he simultaneously abandons the analytical style of his drawings and adopts a more unifying method of sketching.

In

his earlier drawings, Rodin had dissipated the body in single parts, defined by

heavy black outlines. His graphic work dealt with death, sorrow, doubt, pain and

struggle, the tension between inner impulse and outer constraint. But from the

1890´s on, when he can afford to hire a whole range of models and let them move

through his studio, Rodin starts sketching them with swift, generous strokes

that outline the whole body.  See the articles by Kirk Varnedoe on this topic, for

example in Ernst Gerhard Güse (Hrsg.), Rodin Drawings and

Watercolors.

See the articles by Kirk Varnedoe on this topic, for

example in Ernst Gerhard Güse (Hrsg.), Rodin Drawings and

Watercolors.

Instead of drawing from imagination or constructing

the figure from single elements, Rodin now does not take his eye from the model,

his pencil resting on the paper: "Now

look! What is this drawing? Not once in describing the

shape of that mass did I shift my eyes from the model.

Why? Because I wanted to be sure that nothing evaded my

grasp of it. Not a thought about the technical problem of

representing it on paper could be allowed to arrest the

flow of my feelings about it, from my eye to my

hand."

See Anne-Barie Bonnet, Images of Desire, p. 24, for Rodin´s conversation with

Ludovici and an elaborate essay on Rodin´s erotic

drawings.

See Anne-Barie Bonnet, Images of Desire, p. 24, for Rodin´s conversation with

Ludovici and an elaborate essay on Rodin´s erotic

drawings.

Rodin´s hand immediately expresses what he sees in

front of him: women – no men nor mixed couples -, mostly young, naked or

half-naked, dancing, bending over, stretching, sprawling, often drawing up or

spreading their legs so that their uncovered sex shows. In large series of

drawings, Rodin circles around the centre of the female body, the “eternal

tunnel”, or The Origin of the World – the title of Gustave Courbet´s 1866

painting, that still provokes visitors in the Musée d´Orsay.*

* The Origin of the World /L'Origine du monde, 1866, Oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 21 5/8 in. (46 x 55 cm),

Musee d'Orsay, Paris

|