H. de Roos - Rodin´s Approach to Art |

|

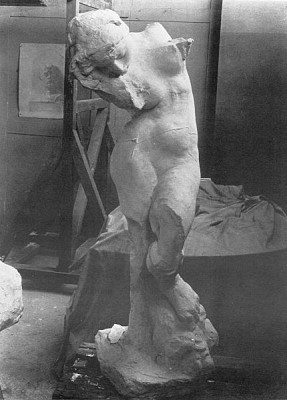

17. The intentional fragment The genealogy of Meditation without arms demonstrates how the artist over the years moved away from the conventional representation of the body. Originally, the figure was part of The Gates of Hell; in 1885 Rodin began exhibiting the Meditation on its own. From 1889 on, a larger version appears as a Muse in his Monument to Victor Hugo, under the name of Les Voix Intérieurs (The Inner Voice) – the title of a series of lyrical poems by Hugo. Simultaneously, it functions as Maria Magdalen, in Le Christ et la Madeleine. |

|

|

Meditation sans bras, plaster |

When Rodin exhibited a plaster model of the Victor Hugo Monument at the Salon of 1897, it showed this Muse as if the arms had brutally been torn off, the knees rudely crushed.

Finally, Rodin decides to create and exhibit mere torsos or single limbs. In 1910, the sculptor explains to Muriel Ciolkowska:"Recently I have taken to isolating limbs, the torso. Why am I blamed for it? Why is it allowed the head and not portions of the body? Every part of the human figure is expressive. And is not an artist always isolating, since in Nature nothing is isolated? When my works do not consist of the complete body (..), people call it unfinished. What do they mean? Michelangelo´s finest works are precisely those which are called 'unfinished'. Works which are called finished are those who are clean - that is all.

|

In 1912, Rodin presents a plaster torso to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, that looks as it had been dug up from the debris of centuries, a piece the 1981 Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin describes as follows:

The intentional ripping away of the head and limbs of this terracotta torso, evident in the traces of violence preserved in the baked clay, has left a vividly modeled fragment, partly Michelangelesque and partly antique in its inspiration, but purely Rodin's in its execution.

|

Torso, 1912, plaster, Metropolitan Museum, New York

|

|

According to the sculptor Henry Moore, who condemned the “factory-like” way Rodin organized the translation of his work into marble, the difference between Michelangelo´s non-finito and Rodin´s partial figure is that Michelangelo would personally develop a figure to a certain point and then leave in this stage, whereas Rodin would send ready plaster models to his stone carvers and request them not to free the figure from the block completely, to accomplish an imitation of Michelangelo´s style.

Whether Rodin´s predilection for the fragment was rooted in his admiration for Michelangelo or constituted a genuine innovative impulse, may remain open to discussion. But undisputedly Rodin propelled this artistic principle more forcefully than any of his contemporaries. For Rainer Crone and David Moos, Rodin´s use of the fragment frees his expression from the narrative connotations and burdensome attributes of the complete sculpture; like the aphorism in Nietzsche´s writings, it would allow for the utmost condensation of his artistic vision, at the same time inviting the spectator to enter into a dialogue with the work and add his own understanding.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notice:

Museum logos appear only as buttons linking to Museum Websites and do not

imply any |

|