|

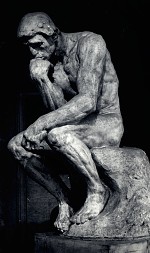

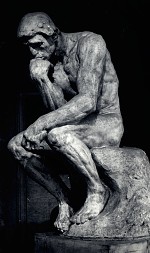

Already in the first year of working on 'The

Gates of Hell', Rodin modeled the central figure

of this great composition:

'The Thinker'.  As

an independent work it became perhaps the best-known sculpture of all

time. As

an independent work it became perhaps the best-known sculpture of all

time.

Seated on the tympanon of 'The Gates of Hell', 'The

Thinker'

watches the whole scene of the Inferno, brooding in contemplation. His athletic body is

twisted in tension from his head down to his curled toes, suggesting a tough intellectual

struggle. While the right muscular arm supports the pensive head, the left hand

is open, as if ready grasp the reality of his vision and to act.

Already

in 1885, Mirbeau noted that both the title and the subject of 'The Thinker'

reminded of Michelangelo's 'Il Penserioso' on the tomb of

Guiliano di Medici. Already

in 1885, Mirbeau noted that both the title and the subject of 'The Thinker'

reminded of Michelangelo's 'Il Penserioso' on the tomb of

Guiliano di Medici.

[Octave Mirbeau, 'Auguste Rodin', in La France,

Paris, 18 Febr. 1885

For complete text, click

here: Page 1+2 Page

3+4 ]

Originally, 'The Thinker' - exhibited in Copenhagen in

1888 as 'The Poet'

- was

to represent Dante Alighieri, the author of the Divina Commedia,

who - according to a popular anecdote - also used to sit and think on a

rock in Florence called Sasso di Dante, watching the Baptistry.

As a portrait of Dante, 'The Thinker' symbolized the intellectual power that created the dramatic world

depicted in 'The Gates':

"In front of this Porte [Rodin explained to a

journalist at the turn of the century], but on a rock, Dante was to be

seated in profound meditation, conceiving the plan of his poem. Behind him,

there was Ugolino, Francesca, Paolo, all the characters of the Divine

Comedy. But something came of this idea. Gaunt, ascetic in his straight

robe, my Dante, seperated from the ensemble, would have had no meaning.

Still inspired by my original idea, I conceived of another Thinker, a

naked man crouched on a rock against which his feet are contracted. Fist

pressed against his teeth, he sits lost in contemplation. His fertile

thoughts slowly unfalled in his imagination. He is not a dreamer; he is a

creator." "In front of this Porte [Rodin explained to a

journalist at the turn of the century], but on a rock, Dante was to be

seated in profound meditation, conceiving the plan of his poem. Behind him,

there was Ugolino, Francesca, Paolo, all the characters of the Divine

Comedy. But something came of this idea. Gaunt, ascetic in his straight

robe, my Dante, seperated from the ensemble, would have had no meaning.

Still inspired by my original idea, I conceived of another Thinker, a

naked man crouched on a rock against which his feet are contracted. Fist

pressed against his teeth, he sits lost in contemplation. His fertile

thoughts slowly unfalled in his imagination. He is not a dreamer; he is a

creator."

[Marcelle Adam, Le Penseur, in: Gil Blas, Paris, 7 July

1904, quoted by Grunfeld, chapter 8, p. 191]

Interpreted this way, 'The Thinker' was detached from his

personal connection with Dante and now is seen to represent the power of thought and

mental creativity more generally. 'The Thinker' not only confirms Dante´s

high reputation as the embodiment of Plato's ideal of the

artist-philosopher: on a more abstract level, Rodin's work associates the creative qualities of artistic

genius with the ability to understand and judge society from a higher

standpoint. Because of his central place high above

the turmoil of the sinners, Elsen even draws a parallel to the figure of

Christ in the Judgement Seat.Another identification of the artist with Christ can be

found in 'Christ and Mary Magdalene'; in

'The

Hand of God', finally, the creative power of the Deity is directly

associated with that of the sculptor.

The elevated position of 'The Thinker' also caused Rodin to enlarge the

shoulders and arms, so that the proportions seem balanced

when looking up to the figure from the ground. Later, when 'The Thinker'

was enlarged and exhibited as a separate work, its lower placement led to an

irritating impression of top-heaviness.

Still during Rodin's life-time, several

critics speculated on the question, what 'The Thinker' was actually

thinking about. With the growing popularity of the socialist movement, 'The

Thinker' was sometimes interpreted as a working class hero, rising from

the fetters of the material world to the heights of class consciousness:

Democracy has had its heroes and

its statues. But these heroes were often no more than bourgeois. (...)

The Thinker of Mr Rodin is, on the contrary, the anonymous unknown

worker, the first to come from among the proletariat, whose native

homeliness the artist has exaggerated, again according to the exigencies

and manner of his art (...)

The proletariat will be flattered ... to see itself endowed with thought -

the proletariat that is so often accused of having only blindness and

instincts.

'Le Penseur' de Rodin, L´Univers et le Monde, quoted by Albert Elsen,

in: Rodin´s Thinker and the Dilemmas of Modern Public Sculpture, Yale

University Press, p. 129

'Le Penseur' de Rodin, L´Univers et le Monde, quoted by Albert Elsen,

in: Rodin´s Thinker and the Dilemmas of Modern Public Sculpture, Yale

University Press, p. 129

Morphologically

spoken, Rodin´s 'Thinker' is the successor of the torso of the

'Seated Ugolino', which Rodin created during his years in Belgium.

Around 1876, Rodin created a further study of a seated man, which can be

seen as a another predecessor to 'The Thinker' (plaster, Nelson-Atkins Museum).

Finally, the giants at the base of the 'Vase

of the Titans' Morphologically

spoken, Rodin´s 'Thinker' is the successor of the torso of the

'Seated Ugolino', which Rodin created during his years in Belgium.

Around 1876, Rodin created a further study of a seated man, which can be

seen as a another predecessor to 'The Thinker' (plaster, Nelson-Atkins Museum).

Finally, the giants at the base of the 'Vase

of the Titans'  deal

with the same complex task of endowing seated heroes with an expression of

activity and strength. In 1901, Rodin recurred to 'The Thinker' while

creating 'The American Athlete'. deal

with the same complex task of endowing seated heroes with an expression of

activity and strength. In 1901, Rodin recurred to 'The Thinker' while

creating 'The American Athlete'.

The first exhibited version of 'The Thinker' – 1888 in Copenhagen – in plaster was 71.5 cm high.

Only in 1902, when Rodin began to have some of his most popular sculptures

enlarged by his helper Henri LeBossé, a monumental version of 'The

Thinker'

was created as well, ca. 1.84 m high. The enlargement was completed by the end

of 1903 and shown in the Spring Salon in Paris 1904. In the Revue

blue of 17 Dec. 1904, Gustave Geffroy commented:"If he were to stand up and walk, the ground under his feet would

tremor and scores of soldiers would part for him."

The

first colossal bronze cast was produced by the young, ambitious founder Hébrard,

who promised Rodin to deliver a cast made after the prestigeous lost wax

method, for the price of a sand cast. This first cast was shipped to the Louisiana

World Exhibition and shown to the public, till Rodin began to doubt

the quality of the patina and sent a plaster cast to Mississippi to

replace the metal sculpture, which was eventually bought by Mr Walker.

In Paris, Gabriel Mourey, publisher of the New magazine Les

Arts de la Vie, took the initiative to organize a public subscription

with the aim to present a monumental bronze cast "to the people of Paris",

to be placed in front of the Panthéon. As a maquette, a bronze

coloured plaster was installed there; on 16 January 1905, this provisory

sculpture was destroyed by a fanatic, called Poitron, who claimed the

thinking poet was mocking at him.

In April 1906, the final bronze version was installed

and remained in front of the Panthéon for 16 years. In 1922, the statue with its pedestal was transported

to the garden of the recently opened

Musée Rodin, allegedly because it would be an obstacle during

public ceremonies.

By now, there are over 20 examples of the colossal

bronze cast, placed in cities all over the world. One of the casts,

manufactured by the Alexis Rudier Foundry, is placed next to the tomb of

Rodin and his wife Rose Beuret in Meudon.

For a detailed overview of all monumental plaster and

bronze examples, see www.penseur.org.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (supplied by The

National Gallery of Art, Washington):

Bartlett, Truman H. "Auguste Rodin, Sculptor." American Architect and Building News (19 January-15 June 1889): 224. Bartlett, Truman H. "Auguste Rodin, Sculptor." American Architect and Building News (19 January-15 June 1889): 224.

Geffroy, Gustave. "Le Statuaire Rodin." Les Lettres et les Arts (1 September 1889). In Vilain, Jacques. Claude Monet-Auguste Rodin: Centennaire de l'exposition de 1889. Exh. cat., Musée Rodin, Paris, 1989: 62. Geffroy, Gustave. "Le Statuaire Rodin." Les Lettres et les Arts (1 September 1889). In Vilain, Jacques. Claude Monet-Auguste Rodin: Centennaire de l'exposition de 1889. Exh. cat., Musée Rodin, Paris, 1989: 62.

Adam, Marcel. "Le Penseur." Gil Blas (7 July 1904). Adam, Marcel. "Le Penseur." Gil Blas (7 July 1904).

Mourey, Gabriel. "Le Penseur de Rodin offert par souscription publique au peuple de Paris." Les Arts et la vie (May 1904): 267-270. Mourey, Gabriel. "Le Penseur de Rodin offert par souscription publique au peuple de Paris." Les Arts et la vie (May 1904): 267-270.

Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. Paris, 1927: 61. Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. Paris, 1927: 61.

Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. 5th ed. Paris, 1944: 24-25. Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. 5th ed. Paris, 1944: 24-25.

Gantner, Joseph. Rodin und Michelangelo. Vienna, 1953: 27-28. Gantner, Joseph. Rodin und Michelangelo. Vienna, 1953: 27-28.

Alhadeff, Albert. "Michelangelo and the Early Rodin." The Art Bulletin 4 (December 1963): 363-367. Alhadeff, Albert. "Michelangelo and the Early Rodin." The Art Bulletin 4 (December 1963): 363-367.

Elsen, Albert E. Rodin. New York, 1963: 52-54. Elsen, Albert E. Rodin. New York, 1963: 52-54.

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 168 Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 168

Spear, Athena Tacha. Rodin Sculpture in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland, 1967: 52-53, 96-97. Spear, Athena Tacha. Rodin Sculpture in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland, 1967: 52-53, 96-97.

European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1968: 148, repro. European Paintings and Sculpture, Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1968: 148, repro.

Tancock, John. The Sculpture of Auguste Rodin. Philadelphia, 1976: 111-121. Tancock, John. The Sculpture of Auguste Rodin. Philadelphia, 1976: 111-121.

de Caso, Jacques, and Patricia B. Sanders. Rodin's Sculpture: A Critical Study of the Spreckels Collection. San Francisco, 1977: 131-138. de Caso, Jacques, and Patricia B. Sanders. Rodin's Sculpture: A Critical Study of the Spreckels Collection. San Francisco, 1977: 131-138.

The Romantics to Rodin: French Nineteenth-Century Sculpture from North American Collections. The Romantics to Rodin: French Nineteenth-Century Sculpture from North American Collections.

Peter Fusco and H.W. Janson, eds. Exh. cat. LACMA; Minn. Inst. of Art; Indianapolis Mus. of Art; Mus. of Fine Arts, Boston. New York, 1980: 334-335. Peter Fusco and H.W. Janson, eds. Exh. cat. LACMA; Minn. Inst. of Art; Indianapolis Mus. of Art; Mus. of Fine Arts, Boston. New York, 1980: 334-335.

Elsen, Albert E. In Rodin's Studio. Ithaca, New York, 1980: figs. 19-22, pls. 23, 24, 165-166. Elsen, Albert E. In Rodin's Studio. Ithaca, New York, 1980: figs. 19-22, pls. 23, 24, 165-166.

Vincent, Clare. "Rodin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A History of the Collection." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Spring 1981): 4-5. Vincent, Clare. "Rodin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A History of the Collection." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Spring 1981): 4-5.

Schmoll, J.A. Rodin--Studien: Persönlichkeit--Werke--Wirkung--Bibliographie. Munich, 1983: 54-58, 66-67, 192-193, 278-282. Schmoll, J.A. Rodin--Studien: Persönlichkeit--Werke--Wirkung--Bibliographie. Munich, 1983: 54-58, 66-67, 192-193, 278-282.

Elsen, Albert E. Rodin's Thinker and the Dilemmas of Modern Public Sculpture. New Haven and London, 1985. Elsen, Albert E. Rodin's Thinker and the Dilemmas of Modern Public Sculpture. New Haven and London, 1985.

Elsen, Albert E. The Gates of Hell by Auguste Rodin. Stanford, California, 1985: 56-57. Elsen, Albert E. The Gates of Hell by Auguste Rodin. Stanford, California, 1985: 56-57.

Jamison, Rosalyn Frankel. Rodin and Hugo: The Nineteenth-Century Theme of Genius in "The Gates" and Related Works. Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1986: 69-122. Jamison, Rosalyn Frankel. Rodin and Hugo: The Nineteenth-Century Theme of Genius in "The Gates" and Related Works. Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1986: 69-122.

Beausire, Alain. Quand Rodin Exposait. Paris, 1988: 99, 105, 156, 185, 195, 220, 242, 265, 266, 271, 286, 302, 307, 314, 315, 349, 366, 368. Beausire, Alain. Quand Rodin Exposait. Paris, 1988: 99, 105, 156, 185, 195, 220, 242, 265, 266, 271, 286, 302, 307, 314, 315, 349, 366, 368.

Fonsmark, Anne-Birgitte. Rodin: La collection du Brasseur Carl Jacobsen à la Glyptothèque. Copenhagen, 1988: 73-78. Fonsmark, Anne-Birgitte. Rodin: La collection du Brasseur Carl Jacobsen à la Glyptothèque. Copenhagen, 1988: 73-78.

Vilain, Jacques. Claude Monet-Auguste Rodin: Centennaire de l'exposition de 1889. Exh. cat. Musée Rodin, Paris, 1989: 174-176. Vilain, Jacques. Claude Monet-Auguste Rodin: Centennaire de l'exposition de 1889. Exh. cat. Musée Rodin, Paris, 1989: 174-176.

Butler, Ruth. Rodin. The Shape of Genius. New Haven and London, 1993: 423-435. Butler, Ruth. Rodin. The Shape of Genius. New Haven and London, 1993: 423-435.

Sculpture: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1994: 208, repro. Sculpture: An Illustrated Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1994: 208, repro.

Kausch, Michael. Auguste Rodin: Eros und Leidenschaft. Exh. cat. Harrach Palace, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 1996: 166-168. Kausch, Michael. Auguste Rodin: Eros und Leidenschaft. Exh. cat. Harrach Palace, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 1996: 166-168.

Porter, John R., and Yves Lacasse. Rodin à Quebec. Quebec, 1998: 78-83. Porter, John R., and Yves Lacasse. Rodin à Quebec. Quebec, 1998: 78-83.

Butler, Ruth, and Suzanne Glover Lindsay, with Alison Luchs, Douglas Lewis, Cynthia J. Mills, and Butler, Ruth, and Suzanne Glover Lindsay, with Alison Luchs, Douglas Lewis, Cynthia J. Mills, and

Jeffrey Weidman. European Sculpture of the Nineteenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, D.C., 2000: 321-326, color repro. Jeffrey Weidman. European Sculpture of the Nineteenth Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. Washington, D.C., 2000: 321-326, color repro.

|

As

an independent work it became perhaps the best-known sculpture of all

time.

As

an independent work it became perhaps the best-known sculpture of all

time.

Already

in 1885, Mirbeau noted that both the title and the subject of 'The Thinker'

reminded of Michelangelo's 'Il Penserioso' on the tomb of

Guiliano di Medici.

Already

in 1885, Mirbeau noted that both the title and the subject of 'The Thinker'

reminded of Michelangelo's 'Il Penserioso' on the tomb of

Guiliano di Medici.

"In front of this Porte [Rodin explained to a

journalist at the turn of the century], but on a rock, Dante was to be

seated in profound meditation, conceiving the plan of his poem. Behind him,

there was Ugolino, Francesca, Paolo, all the characters of the Divine

Comedy. But something came of this idea. Gaunt, ascetic in his straight

robe, my Dante, seperated from the ensemble, would have had no meaning.

Still inspired by my original idea, I conceived of another Thinker, a

naked man crouched on a rock against which his feet are contracted. Fist

pressed against his teeth, he sits lost in contemplation. His fertile

thoughts slowly unfalled in his imagination. He is not a dreamer; he is a

creator."

"In front of this Porte [Rodin explained to a

journalist at the turn of the century], but on a rock, Dante was to be

seated in profound meditation, conceiving the plan of his poem. Behind him,

there was Ugolino, Francesca, Paolo, all the characters of the Divine

Comedy. But something came of this idea. Gaunt, ascetic in his straight

robe, my Dante, seperated from the ensemble, would have had no meaning.

Still inspired by my original idea, I conceived of another Thinker, a

naked man crouched on a rock against which his feet are contracted. Fist

pressed against his teeth, he sits lost in contemplation. His fertile

thoughts slowly unfalled in his imagination. He is not a dreamer; he is a

creator."

Morphologically

spoken, Rodin´s 'Thinker' is the successor of the torso of the

'Seated Ugolino', which Rodin created during his years in Belgium.

Around 1876, Rodin created a further study of a seated man, which can be

seen as a another predecessor to 'The Thinker' (plaster, Nelson-Atkins Museum).

Finally, the giants at the base of the

Morphologically

spoken, Rodin´s 'Thinker' is the successor of the torso of the

'Seated Ugolino', which Rodin created during his years in Belgium.

Around 1876, Rodin created a further study of a seated man, which can be

seen as a another predecessor to 'The Thinker' (plaster, Nelson-Atkins Museum).

Finally, the giants at the base of the