|

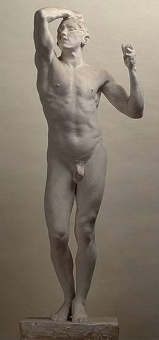

In 1875, when the major decoration projects in Brussels

were nearing completion, Rodin started the work on a life-size male nude

after studies of a 22 years old Belgian soldier named Auguste Neyt. He titled it 'The

Vanquished' and intended to submit it to the Salon. After more than 20

years of apprenticeship and anonymity, he hoped to overcome his status as

a mere handworker and establish himself as a statuaire. Albert

Elsen draws attention to the conservatism of Rodin's aspirations: whereas

the word 'sculpture' is associated with the free-handed creations of Modernism, 'statues' were

life-size standing figures, created

with the intention to have them purchased and displayed by the state. But

exactly this denomiation was denied to Rodin's first attempt: "The

work of M. Rodin is a study, rather than a statue...", wrote the art

critic Tardieu in the magazine Art, in 1877.

Rodin worked on the nude for 18 months. The progress of the work was interrupted by a trip to Italy in February and March 1876 where

Rodin admired the work of Michelangelo in a burst of

enthusiasm. When he returned to Brussels, he finished the sculpture and presented it at the

Cercle

Artistique. Rodin worked on the nude for 18 months. The progress of the work was interrupted by a trip to Italy in February and March 1876 where

Rodin admired the work of Michelangelo in a burst of

enthusiasm. When he returned to Brussels, he finished the sculpture and presented it at the

Cercle

Artistique.

Evidently, the pose was inspired by

Michelangelo's 'Dying Slave' (1514-16, marble, 90" high). Like

Michelangelo's work, Rodin's composition shows a console shape with bent

knees and a hollow chest, transmitting a certain expression of unsureness,

not to say effeminacy.

This impression of temptativeness was augmented by Rodin's decision to have

the spear removed from the character's left hand when his work was

exhibited in Brussels in January 1877. Originally, the model had been keeping a wooden staff in order to keep his

pose for an extended period of time.

But Rodin felt that this attribute interfered with the proper view of

his modelling, so that 'The Vanquished' was displayed with his

left arm suspended in the air. This not only added to the suggestion of

indecisiveness, but also deprived the sculpture of its proposed subject

matter of warfare.

|

Rodin's presentation

provoked consternation at the Cercle Artistique.

Rodin later defended his decision by stating he rather had wanted to

portray a psychological state instead of a literary anecdote: "We

notice that his sculpture expresses the painful withdrawal of the

being into himself, restless energy, the will to act without hope of

success, and finally the martyrdom of the creature who is tormented

by his unrealisable aspirations."

The musculature of this nude was modeled in a

plain naturalistic style without excessive hollows and projections.

"What he wanted was a natural attitude, as realistic as life",

remembered

Neyt. But in the press, the work was not only ridiculed for its vagueness

of subject: incredulous critics accused Rodin of having used plaster casts from

life - a method thought not worthy of an artist. In L'Etoile Belge of

29 Jan. 1877, an anonymous author wrote: |

|

|

"We do not need to examine here whether this plaster was modelled directly on the living

model. We simply wish to point out that the physical and moral dejection of this figure is rendered so expressively that without any indication other than the work

itself, it seems as if the artist wanted to represent a man on the point of committing

suicide."

The persistent artist submitted his work to the

1877 Paris Salon, again without the lance, this time under the title

'The Age of Bronze', only to learn the rumours from Belgium had followed

him.

In Spring 1877, an utterly frustrated Rodin wrote to Rose:

"As you can imagine, I am extremely upset being so near to my

goal! My figure was considered to be so fine by everyone, and now they insist on saying it was modelled from life [...] . I am

demoralized, I am exhausted, I am short of money, I must look for a studio [...]." "As you can imagine, I am extremely upset being so near to my

goal! My figure was considered to be so fine by everyone, and now they insist on saying it was modelled from life [...] . I am

demoralized, I am exhausted, I am short of money, I must look for a studio [...]."

Rodin addressed the chairman of the jury, Eugène

Guillaume, director of the École des Beaux-Arts, for a chance to

clear his reputation:

"Owing to these terrible doubts raised

by the jury, I find myself robbed of the fruits of my labors. Contrary to

what people think I did not cast my figure from the model but spent a year

and a half on it; during that time my model came to the studio almost

constantly. Moreover I have spent my savings working on my figure, which I

had hoped would be as much of a success in Paris as it was in Belgium

since the modeling seems good - it is only the procedure that has been

attacked. How painful it is to find that my figure can be of no help to my

future; how painful to see it rejected on account of a slanderous

suspicion!"

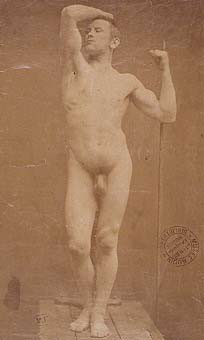

His Belgian friends Félix Bouré and

Gustave Biot contributed testimonies that they had watched Rodin work on

his figure only from the living model. The artist also had photos made of

Auguste Neyt and his sculpture, to demonstrate that the accusations raised

in the Étoile Belge were false, but his evidence was completely

ignored by the jury.

As these pictures show, Rodin made the legs and lower torso of his figure slimmer than the features of the

model; he also made the head somewhat smaller.

To Gsell, Rodin himself later explained the difference between a surmoulage, a life plaster cast of the model, and his own approach as follows:

"Nevertheless,", I [=Paul

Gsell] answered with some malice, "it is not nature exactly as it is that

you evoke in your work." (...)

"But after all, the proof that

you do change it is this, that the cast would not give at all the same

impression as your work."

He reflected an instant and said. "That is so! Because the cast is

less true than my sculpture!

"It would be impossible for any model to keep an animated pose during

all the time that it would take to make a cast from it. But I keep

in my mind the ensemble of the pose and I insist that the model shall

conform to my memory of it. More than that, - the cast only reproduces the

exterior; I reproduce, besides that, the spirit which is certainly also a

part of nature.

"I see all the truth, and not only that of the outside.

"I accentuate the lines which best express the spiritual state that I

interpret.

As he spoke he showed me on a pedestal nearby one of his most beautiful

statues, a young man kneeling, raising suppliant arms to heaven. All his

being is drawn out with anguish. His body is thrown backwards. The breast

heaves, the throat is tense with despair, and the hands are thrown out

towards some mysterious being to which they long to cling.

"Look!" he said to me;

"I have accented the swelling of the muscles which express distress.

Here, here, there - I have exaggerated the straining of the tendons which

indicate the outburst of prayer."

And, with a gesture, he underlined the most vigorous parts of his work.

"I have you, Master!" I cried ironically; "You say yourself

that you have accented, accentuated, exaggerated. You see, then,

that you have changed nature."

He began to laugh at my obstinancy.

"No," he replied. "I have not changed it. Or, rather, if I

have done it, it was without suspecting it at the time. The feeling which

influenced my vision showed me Nature as I have copied her.  Paul Gsell, Rodin on Art and Artistst, Dover Publications, New York, p. 11

Paul Gsell, Rodin on Art and Artistst, Dover Publications, New York, p. 11

As long as he was haunted by the rumour of surmoulage, the road was not

cleared for Rodin's career as an artist sculptor.

On 11 January 1880, Rodin had an interview with Turquet, State Undersecretary

for Fine Arts, who wanted to commission a bronze cast of 'The Age of Bronze', but

needed an

expertise contradicting the accusations raised in Belgium. A commission

headed by deputy inspector Roger Ballu, however, did not believe Rodin had been able to model the work without surmoulage:

"This examination had convinced us that if this statue

is not a life cast in the absolute sense of the word, casting from life

early plays so prponderant a part in it that it cannot really be regarded

as a work of art.."

Together with

Turquet's protégé, Maurice Haquette, Rodin prepared a testimony, dated

23 February 1880, signed by the best-known sculptors of that time, confirming

Rodin's outstanding abilities. After this intervention,

'St. John the Baptist Preaching' and 'The Age of Bronze' are shown in the

Salon; the latter won a third-class medal and was finally purchased by the

state.

In August 1880, it won a gold medal in Ghent.

'The Age of Bronze' by now is a very widespread Rodin

work. It was realized in large, medium and small versions. The first

bronze cast was made by Thiébaut Frères. Allegedly, over 150

bronze casts have been produced by the Rudier Foundry later. The Fine art

Museum of Budapest owns a rare pappmaché version, which was authorised by Rodin.

BIBLIOGRAPHY (supplied by The

National Gallery of Art, Washington):

"Chronique de la Ville." L'Etoile belge (29 January and 3 February 1877). "Chronique de la Ville." L'Etoile belge (29 January and 3 February 1877).

Rousseau, Jean. "Revue des Arts." Echo du Parlement (11 April 1877). Rousseau, Jean. "Revue des Arts." Echo du Parlement (11 April 1877).

Tardieu, Charles. "Le Salon de Paris--1877--La

Sculpture." L'Art 3 (1877): 108. Tardieu, Charles. "Le Salon de Paris--1877--La

Sculpture." L'Art 3 (1877): 108.

Timbal, Charles. "La Sculpture au Salon." Gazette des Beaux-Arts (16 July 1877): 42-43. Timbal, Charles. "La Sculpture au Salon." Gazette des Beaux-Arts (16 July 1877): 42-43.

Bartlett, Truman H. "Auguste Rodin,

Sculptor." American Architect andBuilding News (19 January-15 June 1889): 65, 99-100, 283-284. Bartlett, Truman H. "Auguste Rodin,

Sculptor." American Architect andBuilding News (19 January-15 June 1889): 65, 99-100, 283-284.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Auguste Rodin. Trans. in G. Craig Houston, Rodin and Other Prose

Pieces. London, 1986: 15-16. Rilke, Rainer Maria. Auguste Rodin. Trans. in G. Craig Houston, Rodin and Other Prose

Pieces. London, 1986: 15-16.

Neyt, Auguste. Grand Artistique (April 1922). Neyt, Auguste. Grand Artistique (April 1922).

Cladel, Judith. Rodin: sa vie

glorieuse, sa vie inconnue. Paris, 1936: 108, 114-121. Cladel, Judith. Rodin: sa vie

glorieuse, sa vie inconnue. Paris, 1936: 108, 114-121.

Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. 5th ed. Paris, 1944: 15-16. Grappe, Georges. Catalogue du Musée Rodin. 5th ed. Paris, 1944: 15-16.

Waldemann, Emil. Auguste Rodin.

Vienna, 1945: 22, 73. Waldemann, Emil. Auguste Rodin.

Vienna, 1945: 22, 73.

Seymour, Charles. Masterpieces of Sculpture from the National Gallery of Art. Washington and New York, 1949: 184, note 56,

repro. 168. Seymour, Charles. Masterpieces of Sculpture from the National Gallery of Art. Washington and New York, 1949: 184, note 56,

repro. 168.

Alley, Ronald. Tate Gallery

Catalogues. The Foreign Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture. London, 1959: 210-211. Alley, Ronald. Tate Gallery

Catalogues. The Foreign Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture. London, 1959: 210-211.

Elsen, Albert E. Rodin. New York, 1963: 20-26. Elsen, Albert E. Rodin. New York, 1963: 20-26.

Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and

Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 168. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings and

Sculpture. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1965: 168.

Descharnes, Robert, and Jean-François

Chabrun. Auguste Rodin. Lausanne, 1967: 52-54. Descharnes, Robert, and Jean-François

Chabrun. Auguste Rodin. Lausanne, 1967: 52-54.

Spear, Athena Tacha. Rodin Sculpture in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland, 1967: 39-40, 94-95. Spear, Athena Tacha. Rodin Sculpture in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland, 1967: 39-40, 94-95.

European Paintings and

Sculpture, Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1968: 148,

repro. European Paintings and

Sculpture, Illustrations. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1968: 148,

repro.

Tancock, John. The Sculpture of Auguste Rodin. Philadelphia, 1976: 342-356. Tancock, John. The Sculpture of Auguste Rodin. Philadelphia, 1976: 342-356.

de Caso, Jacques, and Patricia B. Sanders. Rodin's

Sculpture: A Critical Study of the Spreckels Collection. San Francisco, 1977: 38-47. de Caso, Jacques, and Patricia B. Sanders. Rodin's

Sculpture: A Critical Study of the Spreckels Collection. San Francisco, 1977: 38-47.

Butler, Ruth. "Nationalism, a New

Seriousness, and Rodin: Thoughts about French Sculpture in the 1870s." In

H.W. Janson, ed. La Sculptura nel XIX Secolo. Bologna, 1979: 161-167. Butler, Ruth. "Nationalism, a New

Seriousness, and Rodin: Thoughts about French Sculpture in the 1870s." In

H.W. Janson, ed. La Sculptura nel XIX Secolo. Bologna, 1979: 161-167.

Butler, Ruth. Rodin in

Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1980: 32-35. Butler, Ruth. Rodin in

Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1980: 32-35.

Elsen, Albert E. In Rodin's Studio.

Ithaca, New York, 1980: 157-158, pls. 2-5. Elsen, Albert E. In Rodin's Studio.

Ithaca, New York, 1980: 157-158, pls. 2-5.

Butler, Ruth. "Rodin and the Paris Salon." In Rodin

Rediscovered. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1981: 33-34. Butler, Ruth. "Rodin and the Paris Salon." In Rodin

Rediscovered. Exh. cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1981: 33-34.

Vincent, Clare. "Rodin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A History of the

Collection." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Spring 1981): 24. Vincent, Clare. "Rodin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A History of the

Collection." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Spring 1981): 24.

Schmoll, J.A.

Rodin--Studien: Persönlichkeit--Werke--Wirkung--Bibliographie. Munich, 1983: 53-56. Schmoll, J.A.

Rodin--Studien: Persönlichkeit--Werke--Wirkung--Bibliographie. Munich, 1983: 53-56.

Grunfeld, Frederic V. Rodin: A

Biography. New York, 1987: 98-106, 113-114, 125-129. Grunfeld, Frederic V. Rodin: A

Biography. New York, 1987: 98-106, 113-114, 125-129.

Ambrosini, Lynne, and Michelle

Facos. Rodin: The Cantor Gift to the Brooklyn Museum. Brooklyn, 1987: 56-58. Ambrosini, Lynne, and Michelle

Facos. Rodin: The Cantor Gift to the Brooklyn Museum. Brooklyn, 1987: 56-58.

Fonsmark, Anne-Birgitte. Rodin: La collection du Brasseur Carl Jacobsen à la

Glyptothèque. Copenhagen, 1988: 67-69. Fonsmark, Anne-Birgitte. Rodin: La collection du Brasseur Carl Jacobsen à la

Glyptothèque. Copenhagen, 1988: 67-69.

Goldscheider, Cécile. Auguste Rodin: catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre

sculpté. Lausanne, 1989: 114-116. Goldscheider, Cécile. Auguste Rodin: catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre

sculpté. Lausanne, 1989: 114-116.

Butler, Ruth. Rodin. The Shape of Genius. New Haven and London, 1993: 99-112. Butler, Ruth. Rodin. The Shape of Genius. New Haven and London, 1993: 99-112.

Sculpture: An Illustrated

Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1994: 199, repro. Sculpture: An Illustrated

Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1994: 199, repro.

Kausch, Michael. Auguste Rodin: Eros und Leidenschaft.

Exh. cat. Harrach Palace, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 1996: 252-254. Kausch, Michael. Auguste Rodin: Eros und Leidenschaft.

Exh. cat. Harrach Palace, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 1996: 252-254.

Le Normand-Romain, Antoinette. Vers l'Age

d'airain: Rodin en Belgique. Paris, 1997: 246-319. Le Normand-Romain, Antoinette. Vers l'Age

d'airain: Rodin en Belgique. Paris, 1997: 246-319.

Porter, John R., and Yves

Lacasse. Rodin à Québec. Quebec, 1998: 58-59. Porter, John R., and Yves

Lacasse. Rodin à Québec. Quebec, 1998: 58-59.

Butler, Ruth, and Suzanne Glover Lindsay, with Alison Luchs, Douglas Lewis, Cynthia J. Mills, and Butler, Ruth, and Suzanne Glover Lindsay, with Alison Luchs, Douglas Lewis, Cynthia J. Mills, and

Jeffrey Weidman. European Sculpture of the Nineteenth

Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic

Catalogue. Washington, D.C., 2000: 315-317, color repro. Jeffrey Weidman. European Sculpture of the Nineteenth

Century. The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic

Catalogue. Washington, D.C., 2000: 315-317, color repro.

|